How to “True Up” Perceptions of

the Urantia Book’s Cosmology

August 1, 2014

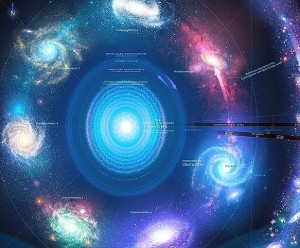

Perhaps the most intriguing aspect of the recent international Urantia conference was strong evidence that a “Urantia mythos” seems to be evolving around the Urantia Book’s cosmology. This is typified by how the conference opened: with a six-minute visionary film that portrays the universe as a series of seven galaxies rotating around the central universe and depicting crisp lines of demarcation between this inner inhabited zone and the four great bands of galaxies in the outer-space levels. (The film’s soundtrack is the sublime “Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun” by Debussy, no doubt chosen to arouse worshipful feelings.) I had also used this excellent film to open my own regional conference in June, but our showing was accompanied by my own commentary that offered qualifications and corrections to its overly simplified and “mythic” picture of the cosmos, and by a panel of scientifically informed speakers.

I highlight this example of “myth-making” because it is one symptom of our movement’s tendency to insulate our book’s less-than-perfect teachings from exposure and comparison to the rapidly expanding knowledge base of today’s evolving post-modern world. And this is one reason I made a  special point of attending the talk by John Causland. While John is not a professional scientist, he is fervent and well-informed student of current astrophysics. It was refreshing to observe how John’s depth of understanding of current science informs his intellectual honesty about the merits and drawbacks of the UB’s teachings on cosmology.

special point of attending the talk by John Causland. While John is not a professional scientist, he is fervent and well-informed student of current astrophysics. It was refreshing to observe how John’s depth of understanding of current science informs his intellectual honesty about the merits and drawbacks of the UB’s teachings on cosmology.

According to Causland, the book’s cosmology is unwieldy because it directly reflects both the scientific achievements as well as the errors and confusion of early 20th century astrophysics (circe 1940); indeed, the book contains many key passages that inject revelatory guidance right alongside erroneous information from a by-gone era in the history of science. On the other hand, it provides a heuristic picture that is still quite useful for us nearly a century later. As he states at his website, UBastronomy.com, “the book’s astronomy is phrased in the language in use at the time of the 1920’s . . . With some amazement, I began to see that the Urantia cosmology actually told a story suggestive of a physical universe that only now we’re beginning to comprehend.”

Causland suggests that the revelators must have timed their teachings to coincide with the advent of someone like Edwin Hubble, who was the first to discover the existence of galaxies outside the Milky Way; Causland speculated that, before the UB’s celestial authors would be able to reveal the size and structure of our universe, our scientists would have needed to first “earn” some rudimentary knowledge of the existence of far-flung galaxies and  other large-scale formations outside of our Milky Way. (This finally occurred with Hubble’s first measurements dating back to 1929, including his famed discovery of the “red shift” showing that these structures were rapidly receding away from.) Yet, Causland stated, the revelators also provided confusing or ambiguous signposts about this extra-galactic universe of universes; this results in part because of the requirement that they utilize human source-authors around whose limited vision they wove specific revelatory insights. In this they were following their mandate not to “over-reveal,” but they also seem to unnecessarily muddy the waters by offering distances and other numbers that are now known to be quite far off. The celestial authors also incorporate and blend several contradictory models of the universe that happened to be extant in the early 20th century. Further, they use terms like “nebula,” “galaxy,” and “universe” almost interchangeably as was done by scientists in this early period. Today these words have far more distinct meanings, and as a result of such complicating factors, the Urantia Book cosmology is no longer reliable in many of its details. In particular, the Urantia text confuses us today by, for example, offering two apparently contradictory models of what constitutes a superuniverse (i.e., the most important large-scale unit of the inhabited evolutionary universe we dwell in, known in the text as the “grand universe”). Some passages depict our superuniverse Orvonton as coextensive with the Milky Way galaxy, while others strongly imply that Orvonton is much greater in size.

other large-scale formations outside of our Milky Way. (This finally occurred with Hubble’s first measurements dating back to 1929, including his famed discovery of the “red shift” showing that these structures were rapidly receding away from.) Yet, Causland stated, the revelators also provided confusing or ambiguous signposts about this extra-galactic universe of universes; this results in part because of the requirement that they utilize human source-authors around whose limited vision they wove specific revelatory insights. In this they were following their mandate not to “over-reveal,” but they also seem to unnecessarily muddy the waters by offering distances and other numbers that are now known to be quite far off. The celestial authors also incorporate and blend several contradictory models of the universe that happened to be extant in the early 20th century. Further, they use terms like “nebula,” “galaxy,” and “universe” almost interchangeably as was done by scientists in this early period. Today these words have far more distinct meanings, and as a result of such complicating factors, the Urantia Book cosmology is no longer reliable in many of its details. In particular, the Urantia text confuses us today by, for example, offering two apparently contradictory models of what constitutes a superuniverse (i.e., the most important large-scale unit of the inhabited evolutionary universe we dwell in, known in the text as the “grand universe”). Some passages depict our superuniverse Orvonton as coextensive with the Milky Way galaxy, while others strongly imply that Orvonton is much greater in size.

Causland goes on to show that our superuniverse simply cannot be a single galaxy that contains a trillion inhabited planets, as some interpreters believe. (As a reminder, the UB states that there are seven superuniverses each containing about one trillion inhabited worlds.) Instead, “Orvonton” is most properly a designation for the massive clump of about a thousand galaxies that we now know to be the Virgo Supercluster. In turn, he also listed and showed us slides of other superclusters with names like Perseus, Centaur, and Formax. These formations of hundreds of galaxies seem to be equivalents to the Virgo group and thus are candidates for entry into the grand-universe catalog of the seven inhabited superuniverses. Before us were slides depicting a set of superclusters now well-identified by astronomers that could well be the ultimate constituents of the grand universe itself! For its part, our Milky Way galaxy is but a small unit of Orvonton, a “minor sector” in UB terminology, containing a mere billion inhabited worlds.

John Causland made one more fascinating point: astrophysics appears to have settled on the startling idea that the universe may contain a gravitational center, which may be akin to something we Urantians know as the eternal central universe. Since the 1980s, astronomers have called this center the “Great Attractor”—an unbelievably massive gravitational vortex toward which the great superclusters are moving. Causland made clear that all such structures are far more vast and complex and somewhat more fuzzy in their outlines than today’s Urantia mythologers have on offer in their sentimental depictions. (Below is a conception by an unnamed Urantian that removes the fuzziness.) Yet Causland declined to take on the other cosmic elephant in the room: the UB’s lack of support for the Big Bang, now well-evidenced in today’s science. But we will cover Causland’s views (and the views of other Urantians) on the Big Bang in a future blog.